From Things to Services: Building the Home-Centered Economic Graph

I. The Need for a Home-Centered Model of Economic Coordination

The home is the most intimate and materially complex environment in most people’s lives. It’s where objects accumulate meaning, where services intersect with identity, and where long-term value — emotional, cultural, and financial — is built. For all its significance, the economy of the home remains underdeveloped and structurally ignored by modern technology. We plan, buy, renovate, maintain, and personalize our homes through a patchwork of tools and services — but no unified system exists to guide that activity. No infrastructure coordinates the relationships between the things we live with, the services we rely on, and the evolving needs of each household over time. There is no graph that understands our home as a whole.

Instead, we’re left with fragments. Search engines can surface lists. Marketplaces can suggest products. Task platforms can find a contractor. These are disconnected, short-term transactions that require constant effort from the user. They don't remember what came before. They don’t know what comes next. And they fail to see the home as a living system — one shaped by personal intention and sustained through coordinated care.

We believe that the home deserves its own model of intelligence — one capable of holding both data and providing continuity. One that treats things and services as linked components of a larger system. One that can help people live well, maintain wisely, and plan with confidence. This white paper outlines our approach to building that model: a home-centered economic graph powered by a Large World Model. It is designed to coordinate the flow of goods, services, labor, and value around the home — and to replace today’s fragmented solutions with a unified, persistent, and actionable system of support.

II. The Deficiency With the Current Economy of the Home

Today’s economy of the home is fragmented by design and neglected by incumbents. It is defined by disconnected tasks, redundant decision-making, and the absence of a reliable structure to support the full arc of domestic life. While modern platforms offer the illusion of convenience, they fail at the one thing that matters most: helping people take real, sustained action.

At a glance, it seems that much has been solved. You can search for furniture on a dozen sites. You can find a cleaner, a painter, or a contractor with a few taps. You can follow a checklist to plan a renovation or move. None of these platforms, however, are truly integrated into your home or your life. They don’t know your space. They don’t remember your past decisions. They don’t help you plan for the future. And they certainly don’t stay with you once a task is complete. The incumbents — search engines, ad-driven marketplaces, gig platforms — are optimized for discovery, not execution. They can list providers, but not guarantee quality. They can host instructions, but not guide follow-through. They present options but offload the burden of judgment, scheduling, coordination, and oversight to the individual.

Worse, they operate in a contextless vacuum. They might know your preferences or demographics, but they don’t know your home — its layout, its needs, its history, or the relationships that define it. They are not spatially aware, temporally aware, or attuned to the cadence of domestic life. They also fail to serve the full range of economic and cultural values that homes contain. When it comes to high-end furniture, artisan-made goods, or legacy home maintenance, the existing platforms collapse. They don’t support informed decision-making around longevity, style, compatibility, or cultural relevance. They offer endless choice without context, and the burden of refinement falls entirely on the user.

Most critically, these systems lack persistence. They do not maintain continuity across time. They don’t remind you of upcoming maintenance. They don’t track the work that has been done. They don’t integrate the aesthetic evolution of your space with the physical upkeep it requires. They don’t serve your home — they simply sell into it. The result is an economy that extracts attention without offering intelligence. One that rewards engagement without responsibility. One that produces friction, not fluency. To build a better system, we must begin by binding services, actions, and long-term knowledge to the home itself as the center of coordination, memory, and meaning.

III. Binding Services and Agency to the Home

A home is never finished. It is in a constant state of becoming — shaped by life events, personal style, seasonal rhythms, and the slow wear of time. Yet most platforms treat the home as a static container: a place to put things, a backdrop for transactions, a node in a logistics network. What’s missing is a recognition that the home is an evolving system — one that requires continuous support, care, and agency.

To truly serve the home, we must bind services to space in a persistent, intelligent way. Every act of maintenance, improvement, cleaning, moving, decorating, or repair is part of an ongoing choreography. It requires people — designers, cleaners, movers, handypersons, delivery crews, specialists — who each bring knowledge, labor, and judgment. But none of these agents operate with shared context. And none of the systems that mediate them are structured around the identity of the home itself. As a result, we believe the home must become the central unit of coordination. It must be a site of agency for the people who live there and for the system that supports them.

In order to do so, we must track its history, understand its needs, surface opportunities, and organize the right actions at the right time. This includes expression through things. The home is a vessel for personal style, where objects — furniture, decor, art, surfaces — reflect identity and intention. These things are both static assets and part of an evolving aesthetic language that changes with the seasons, with life phases, and with the broader cultural context. It also includes execution through services. The home as a site of skilled work, where service providers — designers, installers, craftspeople — bring ideas into form and sustain material quality over time. These services are not isolated events; they are recurring acts of support that shape the life of a space.

When things and services are seen as co-constitutive — as partners in the evolving identity of a home — a new model of domestic agency becomes possible. Instead of starting from scratch for every project, members can be supported by a system that already understands their space, their history, their aspirations, and the relationships that sustain them. This transforms the role of the platform. It no longer simply connects people to products or providers. It becomes a long-term partner in the life of a home — translating goals into action, maintaining memory, and ensuring that the identity of the home evolves in a coherent, supported way. Only by binding service and agency to the home — structurally, contextually, and persistently — can we move from a transactional model to a truly supportive one.

IV. Building the Home-Centered Graph

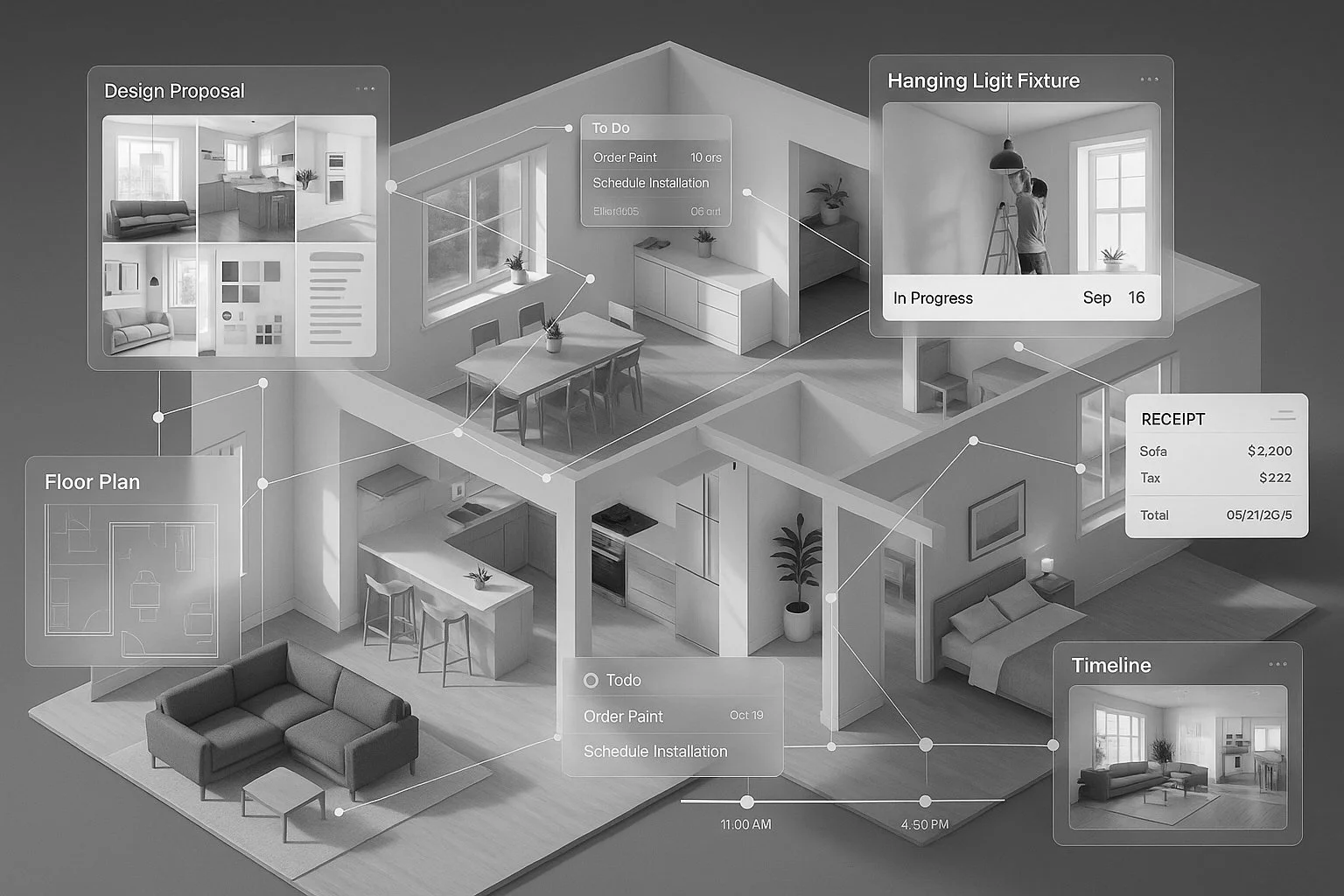

To support the home as a site of persistent coordination, we must create a structure that holds its complexity — one that can represent not just what a home is, but what it needs, what it has been, and what it aspires to become. That structure is the home-centered graph. This graph is the foundation of the Large World Model for Domestic Life. It is a dynamic, relational system that encodes the connections between people, places, things, and services — organized not as isolated data points, but as a living, evolving model of domestic reality. It turns what was once invisible or scattered into something knowable, trackable, and actionable. At its core, the graph is composed of five interdependent layers:

1. Objects

The physical things that populate a home — furniture, fixtures, appliances, heirlooms, artworks. Each object is more than a SKU; it has attributes (size, material, value), relationships (belongs to, matches with, was moved by), and histories (when it was bought, repaired, refinished, replaced). The graph ties each object to its spatial context, lifecycle, and semantic meaning.

2. Agents

The people and organizations that shape a home. This includes the member, family members, guests, landlords, and a network of service providers — movers, decorators, handypeople, technicians, artisans. Each agent is linked to specific actions and levels of trust, with roles that evolve over time.

3. Actions

Everything that happens in and around the home — past, present, or planned. From routine maintenance and scheduled deliveries to renovations and aesthetic upgrades. Actions are not isolated tasks; they are data-rich events with inputs, dependencies, participants, and outcomes. They form the basis for system learning and future planning.

4. Intentions

The goals, preferences, and plans that drive future change. These may be explicitly stated (e.g., “redo the bathroom this fall”) or inferred over time (e.g., a tendency toward vintage wood furniture or seasonal redecorating). Intentions give structure to the otherwise open field of possibilities — allowing the system to recommend, anticipate, and nudge.

5. Place

The home itself — not as a static address, but as a layered spatial entity. Rooms, zones, outdoor areas, and thresholds are all modeled digitally, allowing the graph to spatialize its knowledge and bind all other nodes to physical context. This creates a persistent twin of the home that anchors every action and update in a specific place.

Two dimensions give the graph coherence and depth: time and trust. Time transforms the graph into a memory system. It allows us to see patterns, track wear, anticipate maintenance, and understand how a home evolves — both as a collection of things and as a lived environment with history and rhythm. Trust governs interaction. The graph learns which providers are reliable, which recommendations are accurate, and which sequences lead to successful outcomes. This trust is both systemic (based on reputation and validation) and personal (based on each member’s unique context and preferences).

Together, time and trust allow the graph to move from static representation to active guidance — helping members navigate what to do, when to do it, who to trust, and how to improve their home over time. As a result, the home-centered graph becomes the foundation of a new kind of intelligence: one that learns from experience, refines through participation, and enables a continuous interplay between intention, execution, and reflection — all grounded in the reality of domestic life.

V. Enabling New Types of Exchange

When the home becomes an active node in a persistent, intelligent graph, a new economy becomes possible — one that transcends the narrow constraints of traditional commerce. Rather than treating transactions as isolated events, the home-centered graph enables structured exchanges, informed by context, history, intent, and trust. The goal is no longer to simply buy things or hiring services, but about engaging a system that helps people act with clarity and confidence. The graph enables new types of exchange by doing something today’s platforms cannot: it closes the loop. It doesn’t stop at search, discovery, or inspiration. It carries the user through to execution, adapts to the outcome, and integrates the result into future planning. In the process, key economic interactions are transformed.

1. Scheduling with Context

Most services require more than a match — they require timing, sequencing, and coordination. A successful furniture delivery depends on when the floors are refinished. A painter’s visit depends on weather, occupancy, and the phase of a renovation. Today, this burden falls on the individual. Tomorrow, the graph will coordinate it. With a persistent model of the home and a history of actions, the system can schedule services at the right moment, in the right order, with the right provider. It can anticipate conflicts, surface dependencies, and orchestrate care across time.

2. Recommendations with Relevance

Recommendation engines in commerce are built for volume and engagement — not for trust, precision, or fit. They surface generic trends, not grounded suggestions. By contrast, the home-centered graph recommends based on your actual home, your actual needs, your actual style. It knows the dimensions of your living room, the color of your walls, the presence of children or pets, the pieces you already own. It offers fewer suggestions — but each is more likely to be right.

3. Guarantees Based on Trust

In a graph economy, trust becomes structural as well as reputational. Providers are recommended based on proven performance—having completed similar tasks for similar homes under comparable conditions—creating a more reliable and context-aware system. Feedback is tied to specific actions, outcomes, and contexts — not abstract ratings. The system itself can offer guarantees, insurance, or rebooking based on tracked outcomes — creating a layer of confidence that encourages participation from both members and providers.

4. Local Labor, Global Intelligence

The graph allows small-scale, local providers to compete and thrive by plugging into a system that augments their reach. A local carpenter doesn’t need to master digital marketing — they simply need to deliver excellent work that the system can remember, represent, and recommend. Their services are matched with the right homes, at the right time, without requiring scale for visibility. Meanwhile, global intelligence — from pattern recognition across thousands of homes, to emerging design trends, to supply chain shifts — flows through the system to inform hyper-local actions.

The result is an economy that is neither fully centralized nor fully atomized — but relational, situated, and adaptive. It respects the specificity of place while leveraging the reach of shared knowledge. It values quality over quantity, trust over virality, care over clicks. This isn’t simply a new method for purchasing or scheduling—it’s a new form of participation in the life of your home. It’s guided by a system that enables confident action and makes the connection between effort and outcome clearer than ever before.

VI. Designing Participation and Ownership

An economic graph centered on the home must both facilitate transactions and serve people as contributors, co-creators, and beneficiaries. This requires designing for deeper participation, where members shape the graph through their actions and providers create value through meaningful service. Our approach is to structure this value creation through persistence (each act leaves a trace in the system), relationality (each trace strengthens the network), and alignment (each participant benefits from their contribution). This requires rethinking how platforms function — moving away from extractive models based on monetizing engagement, and toward generative models that reward stewardship, trustworthiness, and quality.

Members should be authors of their own digital twin — able to see, shape, and govern the model of their home. That means transparent systems that explain what is being tracked, and why; controls that allow members to edit, suppress, or reset their graph; portability and interoperability — the ability to carry their home graph across services and contexts; and optional participation in data commons that improve recommendations and services for others. This level of control enables trust — not just in the system’s recommendations, but in its intentions.

Small businesses, independent craftspeople, and local service providers are essential to the home economy — yet they are often excluded from the digital layer. We aim to build an inclusive graph that allows providers to represent themselves accurately, with verified services, style, region, and availability; benefit from reputation systems that are specific, contextual, and fair; build long-term relationships with members through recurring work and coordinated care; and receive structured guidance on pricing, logistics, and service design to improve outcomes. In this model, the platform is not a gatekeeper — it is an advocate. It helps providers thrive in a digital ecosystem without requiring them to master every technical tool.

The system itself must be designed to serve the whole through accountability and incentive alignment. This means developing a revenue model aligned with quality outcomes, not attention or churn; feedback loops that continually refine the graph based on actual results; mechanisms for co-governance, where members and providers help guide the system’s evolution; and transparent metrics for success that prioritize long-term home value and user trust. We envision a future in which the platform earns trust not through opacity, but through structure — where value accrues to those who contribute meaningfully, and where intelligence serves stewardship, not surveillance.

The strength of the platform depends on a living relationship with its participants—one where meaningful engagement makes the system smarter, more responsive, and more valuable for everyone involved. This can occur through rewards for participation and model improvement. This means incentives for members to contribute data, decisions, and insights that improve model accuracy and personalization; rewards for providers whose services generate strong outcomes, reinforce trust, and close the loop between effort and experience; participatory mechanisms that recognize quality planning, curation, and stewardship as forms of economic contribution; and a value structure where those who help refine the system—by sharing knowledge, patterns, and preferences—see tangible benefits in return.

We envision a model where growth is fueled not just by scale, but by participation that enhances quality. As the platform learns, it shares that value with the people and organizations who make it possible—turning everyday actions into a foundation for long-term resilience, shared intelligence, and durable economic alignment. Participation and ownership are the moral and functional core of the home-centered economic graph. Without them, the system would collapse into another extractive network. With them, it becomes a platform for meaningful, reciprocal exchange — one that honors the care we invest in our homes, and builds a better domestic economy around it.

VII. A Graph That Serves the Whole Home

The home is a site of life, care, identity, and work. And yet, most of the systems we use to engage with our homes treat them as passive backdrops — disconnected from the digital services and technologies that now structure the rest of our lives. The home-centered economic graph we are building is an attempt to correct that. Beyond being a new kind of infrastructure, it’s a new way of relating to our living spaces, and of coordinating the effort it takes to sustain them. It brings together the things we live with, the services we rely on, the people we trust, and the aspirations we hold — into a shared model that learns, adapts, and supports us over time.

While improving convenience is important, our broader goal is to support continuity, care, and clarity. It is about reclaiming control over the systems that shape our homes and making them work in service of human intention. It is about creating the conditions in which high-quality work can be matched with real needs, and in which economic value flows back to the people and places that produce it. By binding services to space, by linking people to purpose, and by structuring memory and trust into the fabric of the platform, we create a system that does more than respond — it anticipates, it remembers, it supports, it evolves. In this sense, the Large World Model for Domestic Life should be seen as a co-pilot built to participate in the long, meaningful, and often messy story of what it means to make a home. The graph it powers is the connective tissue of a new economy — one rooted in the real world, scaled to the rhythms of life, and accountable to the people it serves.